"Elsewhere" is about his work in the year 1968 and it shows pictures about the earthquake in Sicily, student riots in Rome, daily life in Cairo, Palestinian fedayn training in Jordan and daily life in Sardinia.

> order the book

A Glance at Life

The perception of an age and the meaning of history are far from objective: there are events that, as time passes, expand or shrink, take a central place or fade into the background of memory. Naturally, some objective criteria do exist – documents and quantitative data, which help to put everything in the right perspective. However, these become inadequate when that which is being evoked is not just an historical reality, but also the atmosphere that made it distinctive. From this point of view, photography plays a vital role, even though it must then be interpreted, because taking a photograph is always a process of choosing, of cutting out a piece of a space at the expense of another, of favouring a “before” or an “after.”

Much has been said and written about the year 1968, especially every ten years, like clockwork, we often get the impression that we are looking at its transformation, by those who strike a rhetorical key and turn it into a myth, but also by those who, on the contrary, denigrate it with suspicious animosity. Like all meaningful moments that changed, if not the world, then at least our way of observing, interpreting and living it, the year 1968 has become the source of an ongoing dispute, which seems to forget the uniqueness of a period characterized by the vital role of collective action, by the importance of music that plays like a soundtrack to the events, by the role of photographic and cinematographic images, which are able to convey the feelings of an entire generation. The iconography of the year 1968 (by which we mean a wider period of time, starting in the mid-Sixties and ending a few years later) is particularly rich, as each demonstration and event was shot by numerous photographers, both amateur and professional. The enthusiasm and the awareness of being the protagonists of an era was infectious, and also influenced those who were capturing it in their films, thus becoming involved in a profession with an undeniable fascination. The Nikon F was like a guitar. Both seemed easy to use because anyone could take a shot or play a C scale, but they were also selective, because few people could play or photograph like a virtuoso. The era of “activist reportage” marks a turning-point in Italy, even compared to the recent past, because so-called Neorealist photography had with a few exceptions been poetic, lyrical, and often social, but not so directly political. The camera became a pointed weapon, to be used in the manner of the great foreign reporters: Eugene Smith, who recounted the lives of simple people, Dorothea Lange, who turned the stories of Steinbeck’s novels into images, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa, who knew how to capture moments in time and transform them into emotions. So much was changing, the world seemed to be shrinking because travel was becoming easier and more economical if one was willing to use army surplus clothes, jeans, sleeping bags, hitch-hiking. At the same time the world’s borders seemed to be expanding, because there wasn’t one place on earth untouched by ferment, discussions, revolutions. The first of many generations that wasn’t called up to fight a war discovered a desire to be together, a curiosity for the world, and even a bitter after-taste of anger.

Fausto Giaccone recaptures the atmosphere of those years, in a far-reaching way that is devoid of any rhetorical slippage. He knows very well that those who visit his exhibition and flip through his catalogue will immediately try to find the photos they expect. So he doesn’t hide the images of the clashes between the students and the police in Valle Giulia in Rome, but they aren’t the sole focus of his investigation, either. There are the handsome faces of students debating at a student assembly, but there is also that unexpected flash of great irony in the almost exasperated expressions of three women scanning a demonstration as it passes under the window where they stand. With the sharpest intuition, Giaccone zooms in on the huge portrait of Mao carried by the demonstrators, whose presence can only just be perceived. Thus the space of the image is divided into two theoretically opposing parts: those who pass by and those who stand at the window, the racket of the new that moves forward and the perplexed silence of those who don’t understand it.

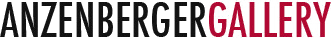

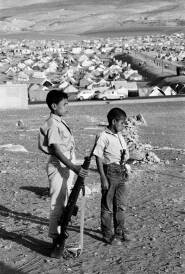

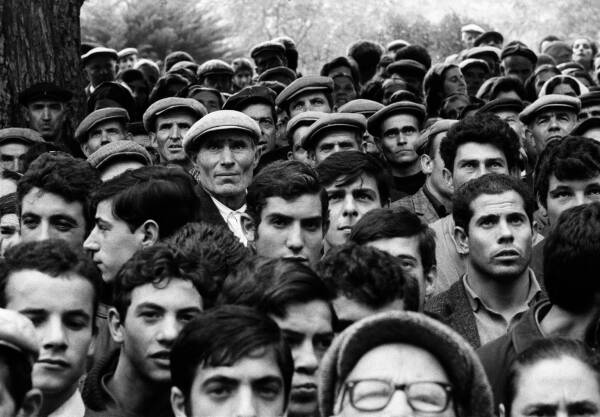

Curious about the events of real life, which is a vital trait of the true photo reporter, Giaccone returned to his native Sicily, to the Valle del Belice, which had been hit by a devastating earthquake in January 1968. His images show a strong emotional involvement, in which the gestures of the men wrapped in blankets and those of the women huddled in black shawls in front of their tents have an ancient flavour of despair. Yet as a photographer he knows how to find the non-conventional image, and shoots four sacred statues saved from the ruins of a church, lined up beside two military tents as if they too were lining up to receive aid. In August, Giaccone is in the Middle East for an article on the training camps of the Fedayn Palestians. It’s beautiful reportage, done with exacting care while living in close contact with the protagonists and, in fact, it is published by the prominent weekly magazine, Paris Match. Yet the interesting thing happens many years later, when Fausto Giaccone is going through old negatives, and realizes that in Egypt he had shot other photos, every bit as interesting, which he had forgotten about, and which nonetheless capture a theatrical and fascinating reality. Among them were images shot from above, of a tailor ironing a shirt with a large iron device, and of some elderly men chatting idly as they sit at a street corner. During his wanderings in the Mediterranean, one autumn morning Fausto Giaccone arrives in Sardinia: the magazine L’Astolabio has sent him to capture the winds of revolt sweeping through many Barbagia villages, the new and unprecedented alliance between workers, shepherds and students, and the widespread rage which is making people hold sit-ins in city halls and clash with the police. Here, too, his images capture moments of widespread involvement by the public: the camera shows young people packed into a cultural centre, studies the crowd at the speech of a much-criticized regional president, and pauses at last, in a splendid image, on a shepherd lounging on a bench at a youth club in Orgosolo, with his legs spread wide and a farmer’s coppola on his head, as he leafs through a political newspaper.

Today, it is of course acceptable to read these images as documents of a past age, but ultimately this is reductive. One would be much better off to think of them as an intense and profound look at life, at people, and at the hopes they had, which still keep them company.

Roberto Mutti